A Field Guide to Complicating Colonialism

Adam Shatz on Frantz Fanon, photoessays and more

Field Guide Vol. 249

Our latest guide is out now! To celebrate, this week’s Field Guide is dedicated to the theme of “Complicating Colonialism.” The issue, produced in partnership with our friends at Coda Story, examines the unexpected ways that the concept of colonialism shapes and impacts daily life—through our food, the languages we speak and the ways we navigate our closest relationships.

We kickoff with Adam Shatz’s fascinating look at the legacy of Frantz Fanon, author of Wretched of the Earth and a key voice in the anti-colonial movement. We also include images from photoessays by Kike Arnal and Justyna Mielnikiewicz, more facts and figures, as well as pieces from Georgia and from even Mars!

We’ll continue to publish pieces from the issue in the coming weeks so keep a look out—and let us know what you think in the comments.

The Algerian war. 1960. Photograph by Dominique Berretty. (Getty Images).

The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon

By Adam Shatz

“History,” in the words of the Marxist literary critic Fredric Jameson, “is what hurts, it is what refuses desire and sets inexorable limits to individual as well as collective praxis.” Fanon had a rare gift for expressing the hurts that history had caused in the lives of Black and colonized peoples, because he felt those hurts with almost unbearable intensity himself. Few writers have captured so vividly the lived experience of racism and colonial domination, the fury it creates in the minds of the oppressed—or the sense of alienation and powerlessness that it engenders. To be a Black person in a white majority society, he writes in one of his bleakest passages, was to feel trapped in “a zone of nonbeing, an extraordinarily sterile and arid region, an incline stripped bare of every essential from which a new departure can emerge.”

Yet Fanon himself had a fervent belief in new departures. In his writing, as well as in his work as a doctor and a revolutionary, he remained defiantly hopeful that the colonized victims of the West—the “wretched of the earth,” he called them—could inaugurate a new era in which they would be free not only of foreign rule but also of forced assimilation to the values and languages of their oppressors. But first they had to be willing to fight for their freedom. He meant this literally. Fanon believed in the re- generative potential of violence. Armed struggle was not simply a response to the violence of colonialism; it was, in his view, a kind of medicine, re- kindling a sense of power and self-mastery. By striking back against their oppressors, the colonized overcame the passivity and self-hatred induced by colonial confinement, cast off the masks of obedience they had been forced to wear, and were reborn, psychologically, as free men and women. But, as he knew, masks are easier to put on than to cast off. Like any struggle to exorcise history’s ghosts and wipe the slate clean, Fanon’s was often a confrontation with impossibility, with the limits to his visionary desires. Much of the power of his writing resides in the tension, which he never quite resolved, between his work as a doctor and his obligations as a militant, between his commitment to healing and his belief in violence.

Fanon made his case for violence in his final work, Les Damnés de la terre (The Wretched of the Earth), published just before his death in December 1961. The aura that still surrounds him today owes much to this book, the culmination of his thinking about anti-colonial revolution and one of the great manifestos of the modern age. In his preface, Jean-Paul Sartre wrote that “the Third World discovers itself and speaks to itself through this voice.” An exaggeration, to be sure, and an inadvertently patronizing one: Fanon’s voice was one among many in the colonized world, which had no shortage of writers and spokespeople. Yet the electrifying impact of Fanon’s book on the imagination of writers, intellectuals, and insurgents in the Third World can hardly be overestimated. A few years after Fanon’s death, Orlando Patterson—a radical young Jamaican writer who would later become a distinguished sociologist of slavery—described The Wretched of the Earth as “the heart and soul of a movement, written, as it could only have been written, by one who fully participated in it.”

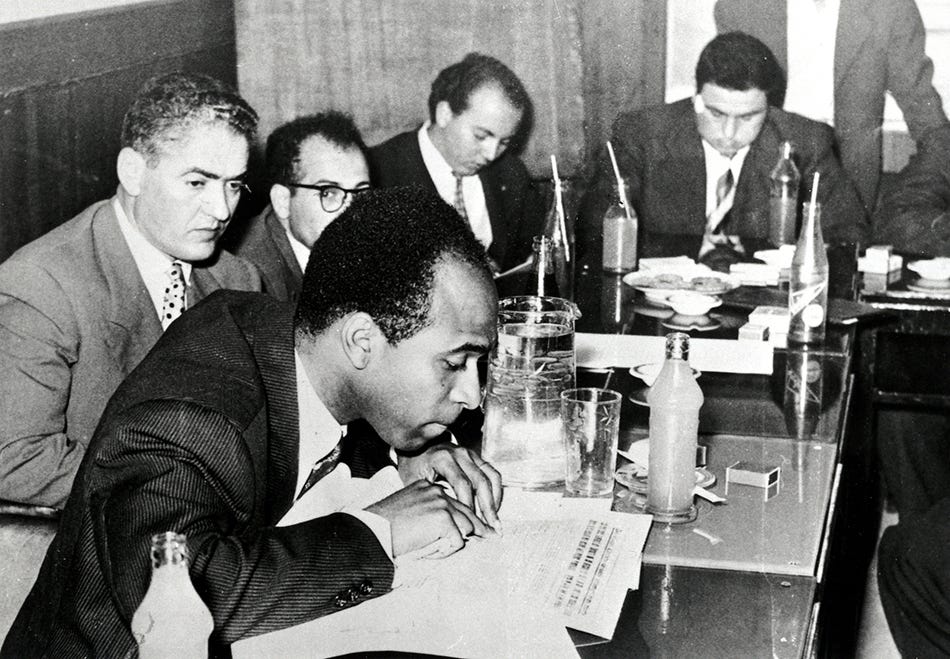

Frantz Fanon at a writers’ conference in Tunis. 1959. (Wikimedia Commons).

The Wretched of the Earth was required reading for revolutionaries in the national liberation movements of the 1960s and ’70s. It was translated widely and cited worshipfully by the Black Panthers, the Black Consciousness movement in South Africa, Latin American guerrillas, the Palestine Liberation Organization, and the Islamic revolutionaries of Iran. From the perspective of his readers in national liberation movements, Fanon understood not only the strategic necessity of violence but also its psychological necessity. And he understood this because he was both a psychiatrist and a colonized Black man.

Some readers in the West have expressed horror at Fanon’s defense of violence, accusing him of being an apologist for terrorism—and there is much to contest. Yet Fanon’s writings on the subject are easily misunderstood or caricatured. As he repeatedly pointed out, colonial regimes, such as French-ruled Algeria, were themselves founded upon violence: the conquest of the indigenous populations; the theft of their land; the denigration of their cultures, languages, and religions. The violence of the colonized was a counter-violence, embraced after other, more peaceful forms of opposition had proved impotent. However gruesome it sometimes was, it could never match the violence of colonial armies, with their bombs, torture centers, and “relocation” camps.

Readers with an intimate experience of oppression and cruelty have often responded sympathetically to Fanon’s insistence on the psychological value of violence for the colonized. In a 1969 essay, the philosopher Jean Améry, a veteran of the Belgian anti-fascist resistance and a Holocaust survivor, wrote that Fanon described a world that he knew very well from his time in Auschwitz. What Fanon understood, Améry argued, was that the violence of the oppressed is “an affirmation of dignity,” opening onto a “historical and human future.” That Fanon, who never belonged anywhere in his lifetime, has been claimed by so many as a revolutionary brother—indeed, as a universal prophet of liberation—is an achievement he might have savored.

Did you know?

In her photoessay “What Makes a Nation?” Justyna Mielnikiewicz documents people in Ukraine, Georgia and Kazakhstan as they try to hold on to their identity in the face of modern Russian imperialism. The above photo was taken in Tbilisi, Georgia, in 2022 as Georgians prepared for the rituals marking the end of winter and beginning of spring. Protestors prepared to burn effigies of Russian president Vladimir Putin. See the full photo essay here!

***

Percentage of citizens today who think their country’s former empire is “something to be proud of”:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Stranger's Guide to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.