Stranger’s Guide explores how politics, power and culture shape daily life across the globe. We believe that local writers, journalists and thinkers are best equipped to explain their political and cultural realities and we publish stories that ask us to listen to the complexities of the world.

Weekly Long Read is for everyone but it’s made possible by our paid subscribers. Thanks to those who support our work, and if you’re not yet a paid subscriber, today is the perfect day to join!

It’s a prime time for sports—between the NFL draft which just closed out, the NBA playoffs, Major League Baseball and the MLS and NWSL seasons in full swing, sports fans have no shortage of content to follow. But while professional leagues dominate headlines, informal sports around the world continue to thrive. In Nigeria, one beloved example is “monkey post,” a local, stripped-down form of soccer often played throughout neighborhoods wherever space is made. With makeshift goal posts and balls—usually whatever materials are accessible at the time—the game captures the joy and beauty of the sport in its rawest form.

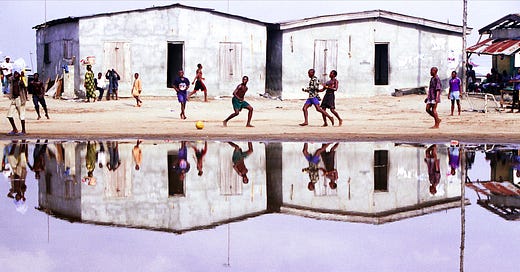

“Monkey Post,” Ayodeji Rotinwa. Photographs by Andrew Esiebo. Stranger’s Guide: Lagos.

If you watch closely, you can tell when an attack is imminent. One player looks briefly to the goal and then surveys the dirt pitch for a nearby teammate. He lifts the ball with his foot, sending it in a diagonal pass over the heads of opposing players. The ball travels quickly, accompanied by a cloud of sand. It lands on the chest of his teammate, who shoots for a goal.

On a warm Saturday morning in Garki, in the Nigerian capital of Abuja, a group of sweaty, energetic men busied themselves like this for hours. The confined space they were playing on was a small patch of dry clay and starved grass. The improvised field was bordered by roads busy with moving vehicles. There was hardly room to pass the ball on the ground without giving it to the opponent, and so the aerial kicks thrived. More than once, the ball overshot the pitch and flew into the path of an oncoming car. Drivers had to brake suddenly to keep the ball from getting caught under their low-riding saloon cars. I expected this near-accident to inspire insults from the motorists who are usually in a haste (to anger or to some unknown destination) and dare anything stand in their way. But football is a beloved sport in the country; the particular variant these men were playing—known as monkey post—even more so. The motorists showed no visible disapproval. All was forgiven as a player retrieved the ball from the road and returned to the field.

Monkey post is a simple form of street football. Originally known as mocking post, the informal game gets its name from the makeshift posts used as goals. The “posts” are usually made of tires heaped on top of one another and set a goal-width apart. Other times, stones, school bags or balled-up clothing are used. The post is an imitation, a mockery of the real thing—but over the years, the pronunciation changed and “mocking” morphed into “monkey.”

The goals for Saturday’s match were made from an impressive set of welded steel posts, which is unusual for monkey post. Two groups of six men, roughly in their 30s, faced off against each other. When one team scored a goal, the other squad had to leave the pitch, and another set of six men took their place. The game I came to watch continued in earnest as the sun began to rise higher, winds stiffening. A “referee” officiated from the shaded sidelines instead of running alongside the men on the pitch. It was hard to distinguish what player belonged to which team, as there were no uniforms. Loyalties shifted, too: I saw one player appear on three different teams as an attacker and “goalkeeper” (no one is stationed at the post, but someone can run back when an attack is coming). Being physically fit is also not essential; the men playing ranged from rail-thin to pot-bellied. Injuries were also inevitable. During one game, a player raised his legs to catch the ball and ended up crashing into the chest of an oncoming player, who hit the field hard. Screams ensued. “E get pikin for house oh! You wan’ kill am?”

•••

The history of monkey post is the history of football in Nigeria. The first recorded game was in the then-British colonial outpost of Calabar, South-South Nigeria, in 1904. According to A Story of Heroes and Epics: A History of Football in Nigeria, by Wiebe Boer, it was played between British sailors and members of Okwaro, a training institution in the port city. The British moved their operations to Lagos, the commercial center, and the sport spread with them.

The game’s popularity was unintentional; the colonial overlords promoted more supposedly “sophisticated” sports like cricket and polo, but they didn’t catch on. “It was the missionaries or the more junior officers that played football because of its socioeconomic association with the lower-class people,” Boer said in a 2018 interview with Nigeria’s daily Premium Times. “And even the fact that Nigerians took football instead of cricket or polo; it was actually a form of colonial protest.”

Also, street football required very little equipment to be played—just a ball and some space.

This spirit carries on to monkey post today. Games are spontaneous, set up on a street, under a bridge, on a farm, on the beach and at a moment’s notice, as long as there is a group willing to play and someone has a ball. The ball itself can be rubber. It can be paper balled up and bound by Sellotape. It can be an energy drink can. Its rules are adaptable, easy to follow.

There are usually four to six players on a team. You can play a throw-in with your feet as opposed to your hands, as in the standard game. When there’s a penalty kick, you play with your heel, with your back to the “post.” The ability to dribble is not a requirement, but it’s just about the only way you will excel in the game. How else can the ball be moved through such narrow spaces? Whoever owns the ball is the king of the game and has the right to choose the best players for his team. Should anyone upset him, he’ll simply pick up his ball, and the game is over.

The “lower-class” reputation of football in Nigeria also carries on into monkey post. The game is most popular in low-income neighborhoods and among students. And it’s just as political now as it was at its inception, though for different reasons. In most cities, where recreational spaces or actual fields are few and far between, monkey post can be read as a form of protest. By playing in public spaces, not fields designed for or provided to them, teams are claiming these spaces as their own. Playing in these spaces is an indirect response to state governments that would sooner approve land for a shopping mall than a football field.

The game can also be personal. For many, it’s an unofficial rite of passage to becoming a man, a way to rubber-stamp masculinity. I was a fairly effeminate child growing up, and football was a way to prove to my critics that I was their equal. When the bullying and teasing reached their peaks at my semi-public secondary school, I decided to play monkey post—even though I wasn’t interested in the game. We played on a dry patch of land that was intended to be the school’s farm. If anything was meant to grow there, we trampled it before it could. We made posts from cans collected from refuse bins. Our ball was paper. I was never very talented. I wasn’t often chosen to play. I scored maybe once. But the teasing diminished significantly.

•••

Monkey post is also susceptible to gamblers. You will find them among the spectators and even the players themselves. Under Marina Bridge, one of Lagos’ busiest thoroughfares, monkey post games are often played below cars passing overhead. Here, bets are routinely made on who will emerge as the winner in a series of games. The gamblers amass their money and sometimes stash it in a pile under one of the posts. The winner takes all. Arguments and even violence break out over who can claim the cash.

Often, there is more at stake. Young players see monkey post as a stepping stone to winning prize money, hoisting a trophy and hearing their names chanted by thousands in a stadium—just like their favorite football stars. Some Lagos neighborhoods where monkey post is popular have produced many national and global stars. Ajegunle, known as AJ City, has yielded Taribo West, Odion Ighalo, Brown Ideye, Samson Siasia and Obafemi Martins. Ighalo was one of the leading goal scorers in the English Premier League. Martins is a well-known, lightning-fast striker who played for heavyweights like Inter Milan. He scored the winning goal in the final that denied Arsenal the 2011 League Cup.

“Monkey post is aspirational,” says Andrew Esiebo, a photojournalist who has documented the game for more than a decade. “You want to imitate the moves of your favorite stars. It is a reimagination of yourself, your social identity through them: how they project themselves, play the game.”

Esiebo adds: “It is also symbolic for community. It’s people coming together. They are bonding, constantly visiting the same place to be entertained, to watch these matches. They might go on to form relationships outside of playing the game.”

When I watched the game that Saturday, there was indeed a camaraderie and generosity of spirit on display. The men asked after each other’s families. One wondered when another had last scored, teasing him about ending the drought in one of the day’s matches. When one player fell injured, members of both his team and the opposing squad ran to make sure he was okay. They chided the offending player, reminding him that the game was just that—a game—and that the man had a family to tend to. And, after all, if he was hurt, how could he join his friends for a post-game beer?

Ayodeji Rotinwa is the deputy editor of pan-African news platform, African Arguments. He covers visual art & culture, social justice and development across West Africa and globally. He has been published in the New York Times, Vogue and Artforum.

Andrew Esiebo is an award-winning visual storyteller based in Nigeria. His work explores sexuality, football, popular culture, migration, religion and spirituality.