Remembering Lewis H. Lapham

Kira Brunner Don remembers the legendary editor and essayist

On July 23, 2024 the American essayist and editor Lewis H. Lapham died. Since then several beautiful obituaries have been written about the great man and I won’t attempt to repeat these, though I certainly encourage reading them. Instead, I want to focus on a very particular time and place where I worked with Lewis and knew him best—the book-filled offices of his last great project, Lapham’s Quarterly.

After a storied tenure of nearly 30 years at Harper’s Magazine, Lewis founded Lapham’s Quarterly in 2007 as a magazine of the history of ideas. The offices were housed on Irving Place just off Union Square in Manhattan. Here, I spent eight years as executive editor and found the offices to be a magical place filled with knowledge, wit, history, literature and cigarette smoke. In those book-lined rooms I got an up-close lesson on how to start a magazine and how to run it with grace. It’s also where I met Abby Rapoport, Stranger’s Guide’s publisher, and my co-founder as we built our own magazine years later.

Back in 2007 I was the first full-time editorial hire Lewis made. On my first day of work, I was greeted by the only other staff members in the office. The first was Anne Gollin, Lewis' rock and long-time assistant. The second was a young intern in flip-flops and cut-off shorts. That was it, that was the entire operation. There was no website, no magazine, no subscribers. Instead there was just the beginning of Lewis’ idea that we cull through the great books and create a digest of thought and ideas. Each issue would be on a new theme, be it war, religion or food.

When I left eight years later, Lewis had built a thriving magazine with 40,000 subscribers and an annual gala—the Decades Ball—headlined by the likes of Tom Hanks and Anne Hathaway. There was a robust intellectual editorial board that met four times a year around a large wooden table to discuss Thucydides, Marx or Hannah Arendt.

But, that all came later. On that very first day of work, Lewis took me out, first to a party at André Schiffrin’s penthouse apartment where he introduced me to Joan Didion before slipping out to a late dinner at Elaine's. Here we sat at what Lewis assured me was the best table in the house. Within minutes the grand dame herself, Elaine, plopped down at our table with a tremendous sigh, as if we were just the port in the storm she’d been waiting for. An endless stream of people dropped by to say hello or to drink or to argue politics late into the night. I was accustomed to a very different crowd—those of small leftist magazines and the New School philosophy graduate students.

“Where am I?” I wondered. “What have I just signed onto?”

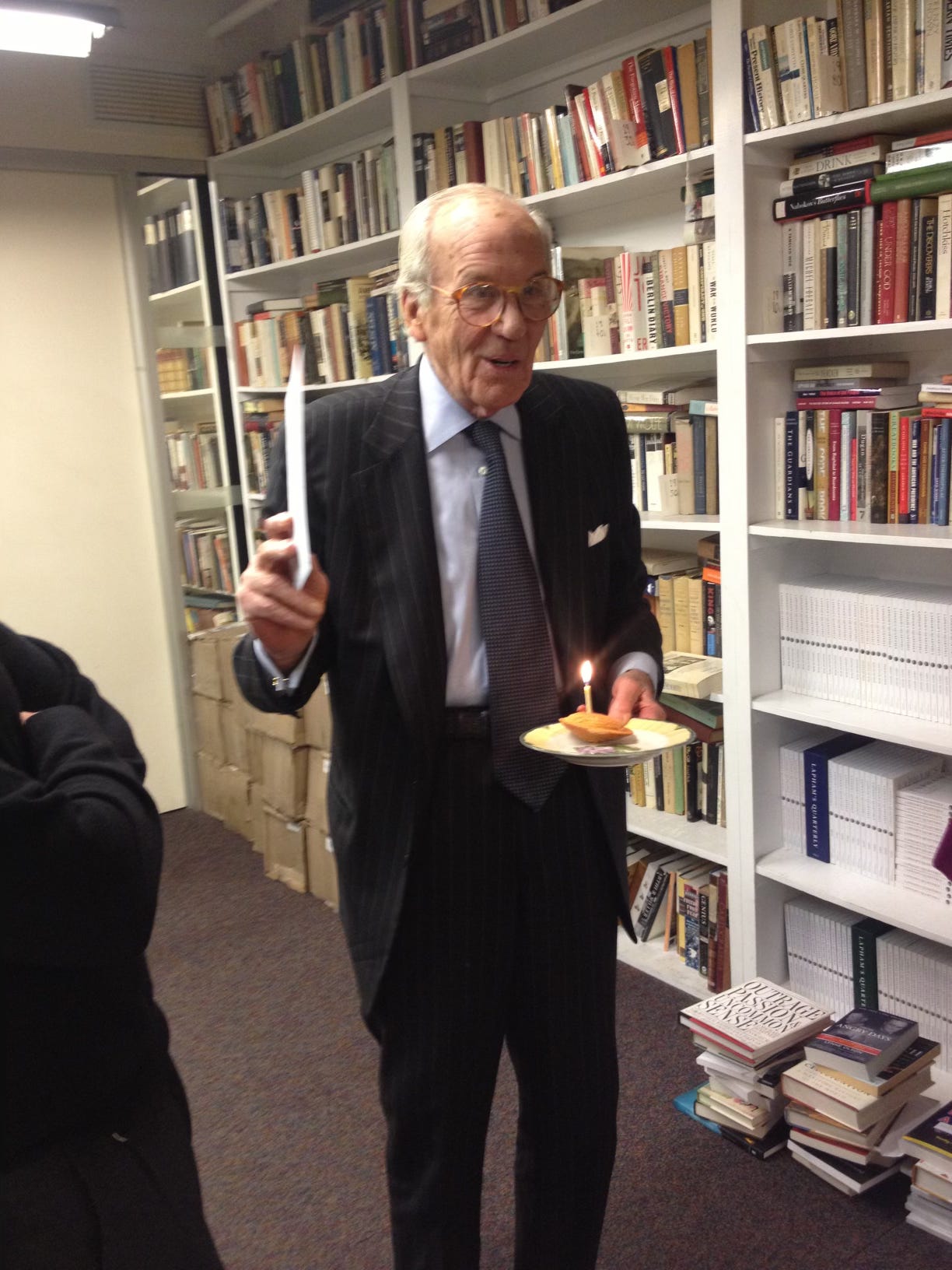

Lewis H. Lapham celebrating a birthday at the Lapham’s Quarterly offices on Irving Place. Photo by Kira Brunner Don.

When Lewis founded Lapham Quarterly he had already been inducted into the American Society of Magazine Editors Hall of Fame. He was already famous as an essayist, editor and author of countless books. But despite all his accolades, those early days at Lapham’s Quarterly had the feel of a 1940s movie about a plucky team of actors putting on a show, a kind of gee shucks folks, let’s make a magazine! On Lewis’ desk next to the ashtrays and the blue folders full of notes, sat the book How to Start a Magazine which was hurriedly tucked away the day the New York Times came to photograph the offices. In those days, I was married to the magazine’s art director and we didn’t yet have kids. So almost every evening after work we’d head off for drinks with Lewis at the nearby bar, Paul and Jimmy’s, where Lewis quickly established himself as a regular. It was here we spent countless hours discussing this nascent publication, its cover, the printer, the feel of an issue and ideas for themes and authors.

Lewis was an incessantly hard worker; he was the first to arrive at the office and the last to leave. Almost every night after work he’d head off to a dinner, a book party or some other glamorous literary event. Although he was already in his 70s, I never saw a man work harder.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly opened with an essay by Lewis that he would painstakingly labor over for weeks; 17 drafts for one essay was not uncommon. Ann Gollin, his trusty accomplice in all things great and small, would diligently transcribe the essays’ he dictated on a small hand-held tape recorder. And then she’d transcribe them again, then yet again, as he crafted and re-crafted each sentence.

Lewis would show everyone in the office his drafts, from the interns to the publisher, asking eagerly “What do you think?” He looked for ideas and input everywhere. He was never an elitist even though he summered in Newport, his pocket squares were crisp and his cufflinks shined. Lewis’ essays poked fun at the American ruling class from his position within the belly of the beast.

For eight years I reveled in Lewis’s beautiful, WASPy, literary, irreverent world. He taught me to value voice and exquisite writing above all else. He taught me to never take the first thought of an author as their best thought, but instead to spend luxurious hours talking over ideas with a writer until we hit upon the right concept.

He wasn’t a saint. He could be selfish and old-fashioned, and at times he demanded loyalty beyond reason. But he was freeing to work for. Famously known as a laissez-faire editor, he never micro-managed. In fact, I’m not sure the words “manage” ever crossed his lips. He let people—his employees, the writers who wrote for him—have a free range. At least once a week he’d open the door of his office and look around the room of editors with a smile and ask “Are you having fun?” Because he was having a ball.

Lewis was fond of saying that “All good editors are pirates” They steal from everyone. And I stole all my best ideas from him on how to start a magazine. So much so, that when Abby Rapoport and I started Stranger’s Guide together we had a blueprint for how it was done. When I told Lewis, I was going to try my luck at starting a magazine with Abby, he did what he always did, bought me a drink at Paul and Jimmy’s and told me not to let anyone steer me off my course or tell me my ideas were wrong. I’m not sure he thought Abby and I could pull it off, but he liked pluck and that was enough for him.

There will never be another like him, but if we are lucky there might be new incantations of his spirit. Or as Lewis liked to say, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme.”

Since his death, only a few days ago, I’ve had countless conversations with old friends from that time, and every conversation inevitably concludes the same way: “Well,“ one of us says “it’s the end of an era.” But to be honest, the era ended long before Lewis died. The New York literary scene is not what it once was—both for better and for worse. But, I could not have had a more splendid boss to waltz me through it than Lewis.

Whenever things got rough in the office—if we weren’t sure where the money would come from or we were behind on a tight deadline—Lewis would look up from his desk, light a cigarette, smile, and say, “Onward, dear heart.”

The Triumph of History over Time, ceiling fresco in the Camera dei Papiri, Vatican Library, by Anton Raphael Mengs, 1772. Vatican Museum, Vatican City. Image courtesy M0tty.

“The Gulf of Time,” Lewis H. Lapham. Lapham’s Quarterly: States of War.

Ed. Note: This was the first essay Lewis wrote for the very first issue of Lapham’s Quarterly.

During my years as editor of Harper’s Magazine, I could rely on the post office to mark the degree to which I was living in what Goethe surely would have regarded as straitened circumstances. Every morning at ten o’clock, I sat down to a desk occupied by five newspapers and seven periodicals (four of them embroiled in politics, the others concerned with socio-economic theory or scientific discovery), three volumes of ancient or modern history (the War of 1812, the death of Christopher Marlowe, the life of Suleiman the Magnificent), a public opinion poll sifting America’s attitude toward family values and assault weapons, and at least fifteen manuscripts, solicited and unsolicited, whose authors assured me in their cover letters that they had unearthed, among other items of interest, the true reason for the Kennedy assassinations and the secret of the universe.