What's out of frame

Abby Rapoport on Ansel Adams, Roger Minick and visualizing nature

Last weekend, I was delighted to attend the opening of the newest exhibit at the University of Texas’ Harry Ransom Center. Curated by Professor Steven D. Hoelscher, “Visualizing the Environment” looks at “Ansel Adams and his Legacy,” surveying the history of environmental photography and raising interesting questions about the role that field might play for our current moment.

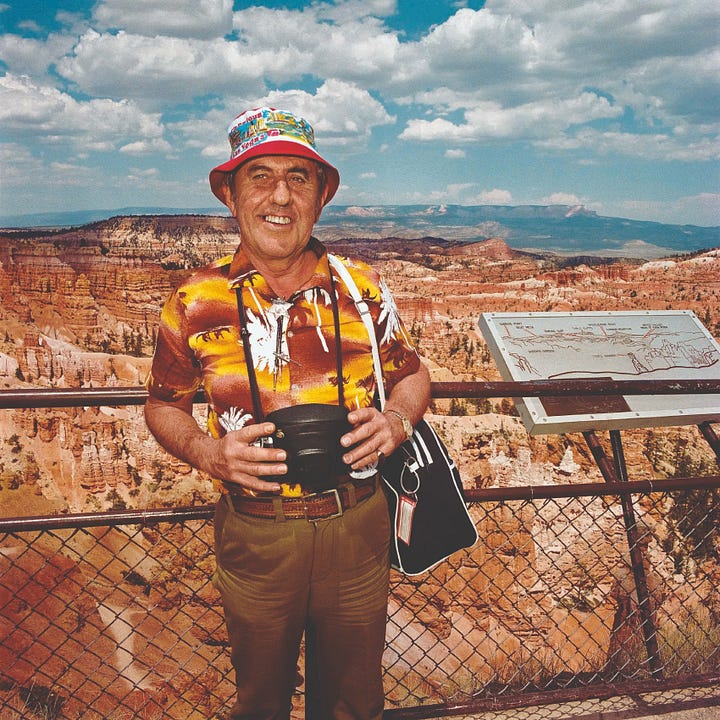

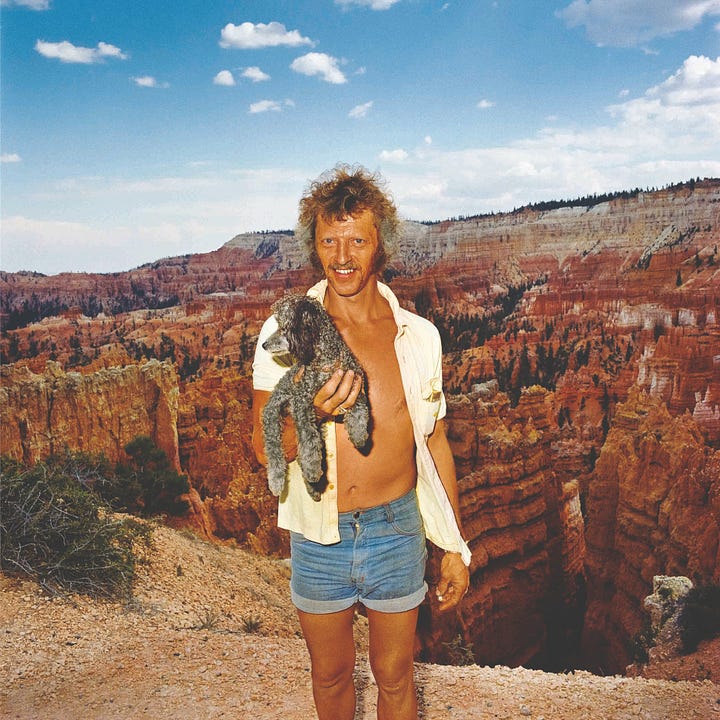

I was initially expecting a tight focus on Adams, so I was surprised to see that the promotional image chosen was not one of his classic, crisp, black-and-white images of a geyser or mountain face. Instead, it was a color image of a lady wearing a slightly silly Yosemite scarf and staring out from the park’s Inspiration Point. I recognized the picture immediately: it comes from the extraordinary series “Sightseer,” by photographer Roger Minick, an Adams’ protege who contributed images from this series to our volume Stranger’s Guide: US National Parks.

I was intrigued.

From “Sightseer” by Roger Minick.

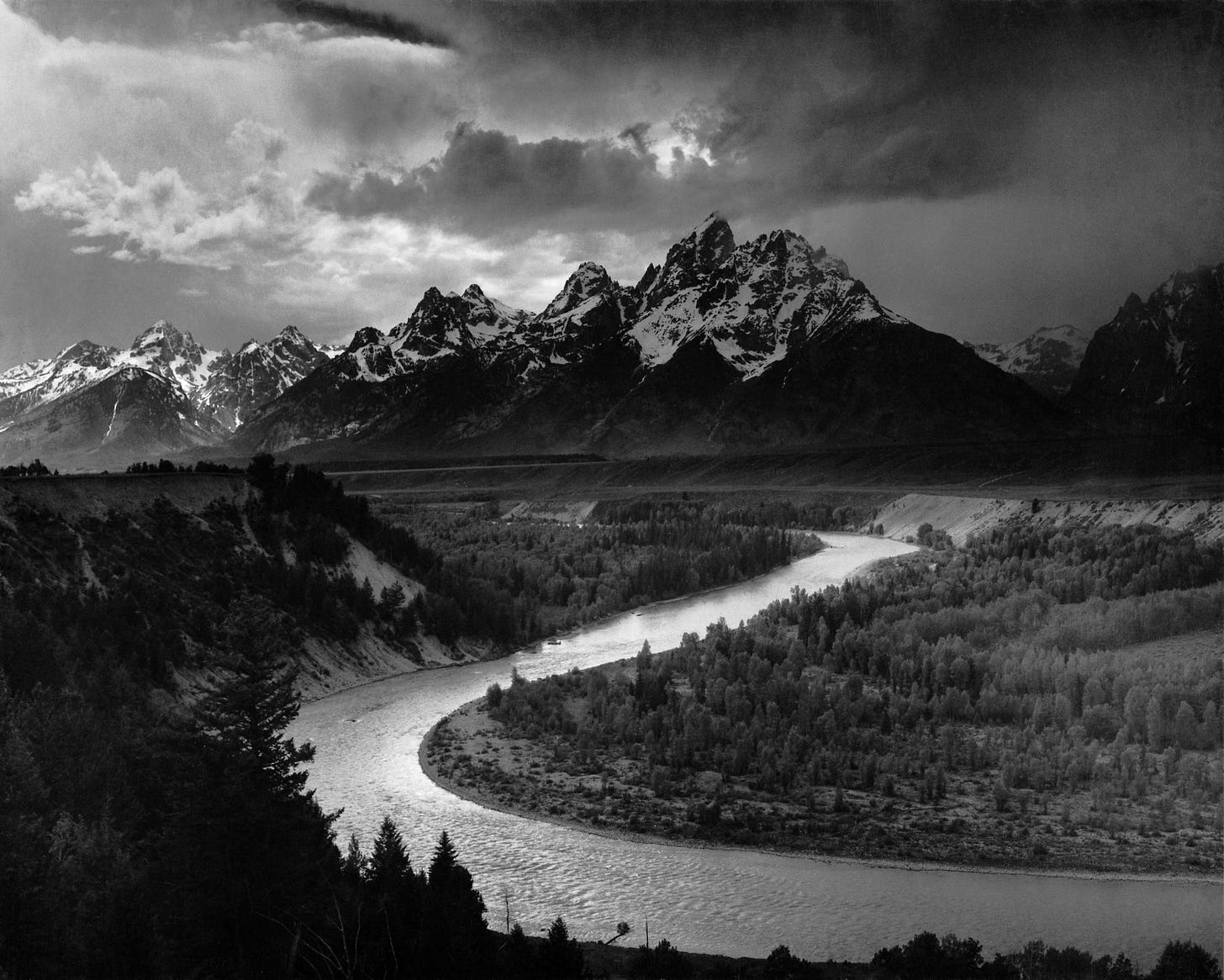

The exhibit puts Adams at the fulcrum of American nature photography, starting with his 1929 portfolio for the Sierra Club and then moving through the later work in which his images acquire increasing contrast and grandeur. These photos, some of which are surprisingly small in size, are largely devoid of humans and instead demonstrate Adams’ “visualization” concept—using a full complement of technical tools to evoke the emotions and experience of the environment. The sky might have been bright and sunny when Adams reached a summit, but the magnitude of the experience would require a dark sky. In Adams’ visualizations, mountains, deserts, waterfalls and glaciers appear as if outside time. People feel puny alongside Half Dome and worldly concerns are petty in the face of the Tetons.

Adams’s work grew out of a tradition pioneered by photographers like Timothy O’Sullivan and Carleton E. Watkins who were sent West to capture the country’s newly acquired lands. In the exhibit, Hoelscher draws particular attention to tensions inherent in these efforts, many of them reconnaissance missions largely built around the conquest of land and the subjugation of American Indians. In images from this time, we see beautiful mountains without the tribes who lived there; alongside stunning vistas, we see the seeming splendor of enormous mining operations and other efforts of US industry.

By contrast, Adams’ “visualization” approach had little interest in military intelligence. His work helped usher in a new chapter for nature photography and became a critical tool for the burgeoning environmental movement. His 1960 book, This is the American Earth, a key environmentalist text he produced with Nancy Newhall, by and large contrasts natural beauty with urban development. In the 1940s his work received support from the National Parks Service rather than from the Department of War. Yet as the exhibit notes, “by removing evidence of the human impact on the earth … Adams presented a romanticized vision of a lost world.”

Ansel Adams The Tetons and the Snake River (1942) Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming. National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the National Park Service.

Enter Roger Minick and his contemporaries. As Minick writes below, in 1976 he was working at an Ansel Adams workshop in Yosemite, where aspiring photographic artists would set up their cameras in front of granite rock faces and wait for approval from the grand master. What caught Minick’s attention was the tourists who would clamber up nearby to get snapshots, often inserting themselves into their photos to show they had been there. Inspired, Minick began a project capturing these tourists as they encountered the natural world.

In Minick’s works it is human messiness—all those puny concerns Adams wipes away—that takes center stage. Even Inspiration Point must make room for our friend in the Yosemite scarf.

Notably, at around the same time photographer Mark Klett began his Rephotographic Survey Project, for which he returned to the sites of significant 19th century photographs and replicated as many of their circumstances as possible, from the season and time of day to the camera position and framing. Klett’s results certainly show a changing environment, but perhaps just as significantly they show the extent to which each image is a human creation, a products of the photographer who envisioned it.

The exhibit (which I strongly recommend if you happen to be in Austin) ends with a gallery of works by contemporary photographers, including the Minick photograph above as well as works by Klett. Adams’ inheritors acknowledge the human influence on our environment, including the manner in which extreme weather is now shaping life.

Of course in our current era of climate change, so much more remains to be said.

In his introduction to “Sightseer,” Minick notes he initially wondered what drew tourists to these different sites. It was only after some time that he began to recognize such places could inspire awe in almost anyone, regardless of the spiritual plane on which they seemed to reside.

As we navigate a rapidly changing environment, I wonder why we do not talk more about climate in terms of the ways the natural world informs our identities as individuals and as communities and our own messy relationships to something greater than ourselves. The strength of Minick’s work is in its implication that everyone can be inspired by natural grandeur.

So too can we be awestruck watching colorful birds fly by our window or watching light filter through tree leaves. In the face of the climate crisis, there’s a critical role for quiet and intimate stories of how we relate to our environments. These kinds of place-based stories are at the heart of the work we’re doing at Stranger’s Guide. And even in the current Instagram-era, those wishing to tell such stories through photography will have a chance to shape a new and critical chapter.

Note: If you’d like to see Minick’s work in print, please consider purchasing our Stranger’s Guide: US National Parks!

“Sightseer,” Roger Minick. Stranger’s Guide: US National Parks.

Before the Selfie

My interest in photographing sightseers began back in 1976 when I was invited to teach at the Ansel Adams workshops in Yosemite National Park. I vividly remember how all the photography students would gather at the famous Inspiration Point overlook, get into position with their cameras mounted to tripods and wait for the grand man himself to move along the line, bestowing his blessings on each student’s composition and choice of exposure. A cacophony of clicking shutters would then follow, with the result, of course, that all the students ended up making nearly identical images. It wasn’t long, however, before I became aware of something else going on at the overlook: waves of tourists were continually arriving at the overlook’s parking lot in cars, buses and motorhomes, thrusting their way through this gauntlet of photographers not only for a clear view of the famous vista but also for the obligatory snapshot of themselves proving they were there. After witnessing this recurring bit of theater over several days, I found myself becoming increasingly fascinated with these visitors, recognizing what a striking cross section of humanity they were. I began to see the visitors as having a specific humanity, their own classification, a genus—Sightseer Americanus. Previously in my photographic career, when my projects took me into the landscape, I had tended to look on sightseers with disdain; certainly I had never considered them a “subject” I would want to photograph seriously. Yet over the course of those days, I began to feel I was witnessing something uniquely American, something that I suddenly very much wanted to photograph.

Throughout my hours of driving and time spent at hundreds of overlooks—from Old Faithful Geyser to the rim of the Grand Canyon, from Niagara Falls to the St. Louis Arch, from the Crazy Horse Memorial to the World Trade Center, from the Alamo to the Washington Mall—there was one question that continued to press upon me for an answer. What was it that motivated people, by the hundreds of thousands, at great expense of time, money and effort, to visit these far-off places of wonder and curiosity? I must confess that there were times in my travels, squeezed elbow-to-elbow with my fellow travelers, that I viewed their presence at the overlooks as nothing more than another example of mindless, boorish behavior. I thought they were there simply to get their pictures taken as quickly as possible, the one tangible validation of their trip, and then head on to the next overlook, the next campground, motel, bus stop, then home—the experience at any one of the dozens of overlooks remembered only later through a snapshot they barely recalled taking.

But in the end, I came to believe that there was something more meaningful going on—something stronger and more compelling, something that seemed almost woven into the fabric of the American psyche. I witnessed this most dramatically when I watched first-timers arrive at a particularly spectacular overlook and see their expressions become instantly awestruck at this, their first sighting of some iconic beauty or curiosity or wonder. After seeing this happen innumerable times, I began to compare what I was seeing to religious pilgrimages, where the pilgrims are not just making a trip to make a trip, or simply to return home with some tangible piece of evidence that they were there—the snapshot; they have instead come seeking something deeper, beyond themselves, and are finding it in this moment of visitation. For, as with all pilgrimages, they have made the journey, they have arrived and they are now experiencing the quickening sense of recognition and affirmation, that universal sense of a shared past and present, and, with any luck, a shared future.

Wonderful photography!